HKØNA DXpedition 2012

Written by Bob Allphin, K4UEE

195,000 QSOs….WOW ! How does a DXpedition make that many contacts? Well, it’s just simple math: have a lot of radios and antennas, a lot of days on the air and enough operators to keep making QSOs day after day. And that is exactly what we did……piling up about 10,000-15,000 contacts each day until time to go home.

But that wasn’t always the plan. Originally when the DXpedition to Malpelo was first announced, there were to be six Colombian (HK) operators and four foreign operators. When Gregg Marco, W6IZT and I were invited to join the team, we recommended expanding to fourteen total by adding some more foreign operators. Suddenly one day, we saw on the DXpedition website that we were now co-leaders. It was news to us, but in the end we played important roles in the operation. Gregg was asked to handle equipment procurement, antennas and the IT requirements. I was to handle fund-raising, public relations, and help build and manage the operator team.

In October 2011, three team members conducted a recon trip to the island. While on Malpelo, the Colombian Marine contingent stationed there had shown Jorge HK1R (the DXpedition organizer), Faber HK6F and Sal HK1T the way to the top of the highest peak on island. This literally opened up a whole new world to them…..they had a 360º view of the entire radio world. All the previous DXpedtions to Malpelo had been conducted from the only flat spot on the island on the Eastern side, about 1/3 of the way up. This location was blocked radio-wise from about North, through West all the way to South as the steep mountain walls rose sharply another 600 feet from this normal QTH. As a result, contacts in the past with the West coast of the USA, Japan, Asia, the Pacific, Southeast Asia and VK/ZL were hard to come by. They now saw a way to change that! In fact, Jorge decided we had a chance at the QSO world record for a non-hotel, non fly-in type DXpedition (that is the record that was set by the Ducie Island DXpedition, VP6DX in 2008). After their return, Jorge contacted Gregg and me and said we needed more radios, amplifiers, antennas, generator and operators.

In October 2011, three team members conducted a recon trip to the island. While on Malpelo, the Colombian Marine contingent stationed there had shown Jorge HK1R (the DXpedition organizer), Faber HK6F and Sal HK1T the way to the top of the highest peak on island. This literally opened up a whole new world to them…..they had a 360º view of the entire radio world. All the previous DXpedtions to Malpelo had been conducted from the only flat spot on the island on the Eastern side, about 1/3 of the way up. This location was blocked radio-wise from about North, through West all the way to South as the steep mountain walls rose sharply another 600 feet from this normal QTH. As a result, contacts in the past with the West coast of the USA, Japan, Asia, the Pacific, Southeast Asia and VK/ZL were hard to come by. They now saw a way to change that! In fact, Jorge decided we had a chance at the QSO world record for a non-hotel, non fly-in type DXpedition (that is the record that was set by the Ducie Island DXpedition, VP6DX in 2008). After their return, Jorge contacted Gregg and me and said we needed more radios, amplifiers, antennas, generator and operators.

With that decision, the die was cast. I quickly sent a few emails and made a few telephone calls and issued some more invitations and we grew the team to twenty operators. Like most DXpedition leaders, I have a list of people that I have been on DXpedtions with before and know people I can trust to do a good job under difficult circumstances. Also, I place a high value on compatibility among team members. I believe no one has the right to ruin another person’s experience. Looking at the operator HKØNA operator list, you will see relationships going back to 1997 that began at VKØIR. I did inherit some operators from the original team. Although they had little DXpedition experience; they were all successful contest operators and were good guys.

Gregg, George N4GRN and I flew to Cartagena, Colombia the first week of November to meet with our Colombian counterparts and to make some critical decisions. We found that we were all quite compatible and made friends easily. We were pleased that we all shared the belief that safety was our primary goal. We would do everything possible to protect our team from injury or worse. The island is nearly vertical and difficult to access from the sea. In previous DXpedtions there have been incidents where team members have been injured and there was one near-fatality. Faber, HK6F is a safety/rescue expert in his profession and George, N4GRN was on a cave rescue team years ago. Together they devised a plan to install a winch system to hoist people and equipment safely onto “El Tangon”. This is the structure put in place by the Colombian Navy some years ago to facilitate the re-supply and changing of the personnel stationed on the island.

Additionally they decided to install safety cables at the more dangerous and difficult parts of the climb to further reduce risk to the team members. As with most of the equipment used on the DXpedition, the necessary cables, clamps, harnesses, screws, etc. were purchased in the US and shipped to Colombia via a freight forwarder in Miami.

Additionally they decided to install safety cables at the more dangerous and difficult parts of the climb to further reduce risk to the team members. As with most of the equipment used on the DXpedition, the necessary cables, clamps, harnesses, screws, etc. were purchased in the US and shipped to Colombia via a freight forwarder in Miami.

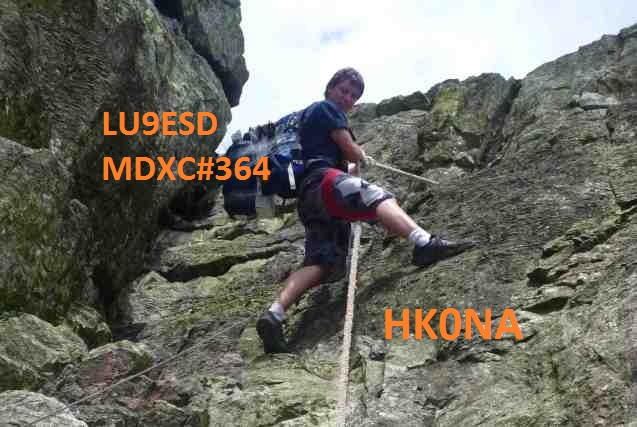

Using a Yahoo Group reflector for the team, we all became better acquainted as the plans for a successful DXpedition were discussed, modified and finalized. There were a lot of emails from our team doctors (WØGJ, KØIR and primary physician K9SG) urging us to get our old bodies in shape. The youngest on the team was 24 (LU9ESD) and the oldest was 74. This was to be a physically tough adventure for most of us.

Jorge convinced four of our team to go to Malpelo prior to the full team’s arrival in order to establish the operating sites, put up the antennas, set up radios, amplifiers and the generators. They left home on Christmas day and traveled to Malpelo on the monthly Navy re-supply ship. Although the dry season was supposed to begin in December, they were plagued with terrible weather. It rained almost every day and some days it poured and poured. They did manage to completely prepare Op. B (baja) and get about 40% of the antennas and equipment up to Op. A (alto) at the mountaintop. On January 10th, when it was apparent that they had done about all they could do and further progress was strictly weather-dependent, we told them to begin using the official HKØNA call sign. Previously, they had used their own call signs and made about 1,200 QSOs. After they began using HKØNA, they made about 11,500 QSOs prior to the main team arriving on January 21st. This strategy was part of our overall strategy to break the VP6DX record, but more importantly that decision gave DXers more time to get into the log.

The main team met in Bogotá the evening of January 18th. It was the first time that some of us had met and it was quite fun and festive. The bar bill was large! Next morning we flew to the port city of Buenaventura and checked into a beautiful, classic and very old hotel. We were checked in by noon and began our first team meeting shortly afterward. This was the first time that we could all be together to discuss all that needed to be discussed: the itinerary, safety procedures, equipment, antennas, power, getting on and off the island. Additionally, Glenn WØGJ went over the computerized scheduling program that he and KØRC had developed. It is really quite sophisticated and looked like it was going to solve our scheduling challenge. The doctors each talked with us about our responsibilities to both ourselves and to our teammates. The biggest concern was a fall and a broken limb and sun-related illnesses. We had several fellas have a problem on Desecheo and we didn’t want to go though that again. It is all about staying hydrated. We were cautioned over and over to look for warning signs in our teammates. We had set up a water cooler and icemaker at Op. B. That would make it easier to get a cool drink of water and help prevent dehydration. Also, having most of the outdoor work already completed at Op. B would keep us out of the sun as well.

Our charter vessel, the SeaWolf, is normally used to transport scuba divers to Malpelo. It is a world-famous dive destination because of the diverse undersea life including huge schools of hammerhead and silky sharks. On occasion, there are whale sharks found there too. It was a 24-hour transit to Malpelo. We left the hotel at midnight and boarded the vessel about 0100 am. After a quick briefing we hit the sack and the SeaWolf departed at 0400. I only remember the sound of the engines as we left Buenaventura and when we were in the open sea, the motion of the boat changed significantly. We had rough seas all the way and most of the fellas slept late and missed breakfast. During the day, people would come topside for a look around and say “hi” to the few guys hanging around and then go back to their bunks.

At 0500 the following morning, we heard the engines slow and we raced topside to get our first glimpse “the rock”. It looked just like the pictures except bigger. As the sun rose, we began ferrying men and their personal gear to “El Tangon”. Some climbed the rope ladder; most were hoisted up like sacks of potatoes using the hoist system. Then, usually in groups of two or three, people would begin the climb to the marine base, the location for our Op. B. As you might imagine, a few folks made it in 25 minutes or so and bragged that they made no stops….I, on the other hand, took 45 minutes and made eight stops to rest and hydrate. Eventually everyone was up and we saw our home for the next sixteen days. Things were pretty much ready to go. All the antennas were up, the radios and amplifiers were neatly placed on tables that lined the wall of the small building Jorge had negotiated for our use. Six stations in all…ready to go. All this because four guys (HK1MW, HK6F, HK1N and HK1T) went early to do the setup. We call them the “Fabulous Four”. We are all indebted to them and thankful for their sacrifice. That should include DXers worldwide because you had a longer opportunity to work us…and hopefully put a ‘New One” in your logs.

While Gregg W6IZT, loaded the final version of N1MM into all the computers, several men set up the two sleeping tents, while others made interference checks among the stations. We were on the air at noon (local) the same the day we arrived. The pileups were huge as the #12 “most wanted “ DXCC entity came on the air with six stations simultaneously. We implemented the computerized schedule that had been so painstakingly-developed and began to settle into “DXpedition mode” i.e. sleep, eat, operate and do chores. The pileups would continue non-stop for fifteen days.

But we still had to get Op. A at the mountain top up and running. We had purchased a sturdy operating tent at the last minute and checked it as “excess” baggage on the trip down. Our fear was that the operating site was so exposed to the weather, and because the “Fab Four” had experienced 60 mph winds at the top the previous week, we were just uncomfortable with the existing complement of tents. The tent, a single generator, a couple of antennas, masts, and personal gear were carried to the top. Several of our guys and 4-5 marines did the heavy lifting. The site was 600 feet above Op. B, but the climb was circuitous and dangerous. In those places where a slip and fall would have sent a man tumbling down the mountain, the Fabulous Four had installed safety lines. It was the last 50-60 feet that were the scariest. It was virtually straight up and you pulled yourself up with a rope that had been tied in place. Fortunately, the footing was secure rock and there were crevices to use as steps; but without the rope it would have been impossible for anyone other than an experienced mountain climber. I was warned never to look down and I didn’t until I reached the top. I only went to Op. A once and am glad I did because I can appreciate the difficulty of the climb and the danger that some very special team members undertook to keep those four stations on the air. There were 6-7 guys who basically manned Op. A off and on for twelve days. They would go up and stay 2-3 days, operate and operate and sleep little. Then they would come down, shower, and eat a meal or two, get some asleep and go back up. I began referring to them as the “Iron Men”. They were Jorge, HK1R the DXpedition organizer, Franz, DJ9ZB, Manu LU9ESD. Peter PP5XX primarily. Ralph KØIR, Glenn WØGJ, Steve VE7CT, Bob N6OX, Sal HK1T, Faber HK6F and Bolmar HK1MW spelled them on occasion.

From Op. B we had a clear shot to US east coast, Europe and Africa. They were loud on Malpelo and we were loud on their end. Stations “behind” the mountain were significantly weaker, but workable, if they could hear us. Asia was our biggest challenge, but from Op.A it was a chip shot. I was told over and over that JAs were 20-30db over S9 on some bands while barely readable below at Op. B. All told we put made 12,500 QSOs with Japan and for many of them it was a “new one” for sure.

Because not all of out team was either able or inclined to pull shifts at the mountaintop, our computerized scheduling that had all been done in advance was out the window. We took a step back in time and used pen, paper and chart on the wall method. The fellas at Op.A did their own scheduling based upon who was “on top” and kept the three HF stations and a 6m station on the air almost around the clock. They had fewer operators to share the duty…so they worked harder!

Down below, we assessed our talent and the operator’s interests and crafted a schedule that gave everyone shifts that seemed to satisfy everyone and maintained our QSO rates. When we realized that the “tent and generator” QSO record was within reach, we had a meeting and I asked if we should modify the schedule and begin using our more experienced operators on more shifts and reduce the shifts of the less experienced guys. To a man, they said yes…let’s do it…. let’s go for it. So for the next six days, some fellas were pulling four to five three-hour shifts each 24-hour period while others were reduced to one or two. I want to thank those fellas for sacrificing their enjoyment for the good of the team. They know who they are! This enabled us to keep the daily rates high even as the demand for QSOs and the pileups began to diminish.

It seemed we would never get to the record. We would collect the logs at each station once per day around noon and then post the cumulative number. We would be making between 12,000 and 15,000 QSOs per day but it seemed we would never get there. It is easy to set a goal and a number of QSOs you want to make, but you must actually make those QSOs….one at a time.

Op.A was shut down on Feb. 3rd and our guys and some of the marines brought everything down the mountain. It was very sad in a number of ways as their success from up there was critical to our overall QSO count, but I know the “Iron Men” really didn’t want it to end. They were literally at the top of world with a view and radio conditions that were unequalled.

Now we had everyone back at Op. B and nowhere to sleep everyone…. to say nothing of the fact that we now had too many operators. Jorge and I talked and we agreed to send the Op.A guys and a few others to the SeaWolf. They were entitled to some R & R and maybe a beer or two. So the crew that had worked together at Op. B for all those days stayed on the air another 36 hours and added thousands more QSOs to the logs. We kept four stations on the air until noon local time on Feb.5th and we were completely off the island by 7:00 pm local. The QSO total was 195,000 plus. We couldn’t believe it ourselves….still can’t!

Just a quick word about the team. We had twenty men from six different countries, with the majority coming from Colombia and the United States. We spoke four different languages, although English was the language of convenience. There were times when we thought we were being understood and times we thought that we understood what was being said to us. Well, it always didn’t work out that way. There were misunderstandings and differences of opinion and different cultural challenges, but to the team’s credit…we worked through all of those challenges and all went home as friends or as the Colombians prefer…compadres ! (translation…better than a friend).

It was a great adventure and everyone returned home safely with stories to be told and retold for years to come.

A word about DXpedition funding, especially as it concerns the rare “most wanted” entities. They are rare for a reason…usually there are political restrictions or they are geographically difficult to reach — or both. It’s common for the DXpedition team members to pay 50-70% of the total costs of these kinds of DXpeditions, but the remainder must come from DX Clubs, DXers and of course, DX Foundations. . I urge you to please continue your support your other favorite DX Foundations and DX Clubs as well as make direct contributions to the DXpedition.

TX7W Austral

TX7W Austral T32EU East Kiribati

T32EU East Kiribati